Iceland

Exotic Foods, Human Migration

Food is great way to experience any place you travel to. But Icelandic specialties will require Viking like courage and a suspension of your sense of smell. The most stomach churning is Hákarl – putrefied shark meat buried underground for upto six months. The stench can be unbearable – like ammonia – and the after taste requires to be washed down with Brennivín, sledgehammer schnapps made from potatoes and flavored with caraway. Someone long ago discovered that certain shark meat could not be eaten fresh and decided to bury it in sand, let it decompose, and try it again six months later. How human beings research these things is a great mystery to me. Then there is bl?ðmör, sheep’s blood pudding packed in suet and sewn up in the sheep’s stomach. And finally Svið, singed sheep’s head, sawn in two, boiled, and eaten fresh or pickled. The king of Icelandic gastronomic adventures is Sursadir hrutspungar, pickled Ram’s testicles. All of a sudden you feel grateful for the great invasion by Macdonalds, Pizza Hut, and Subway.

Human migration is always fascinating. Seeing people living in a context completely different from their usual one is always intriguing. As the editors of Lonely Planet are fond of saying, “Ever since our first, faltering, upright steps, humankind has traveled. Everywhere is migration, exploration, pursuit. Terrible things have been caused by this restlessness, but it is also the source of much that is extraordinary and wonderful.”

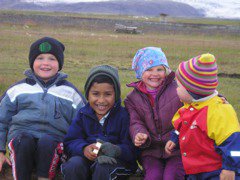

It is this great migration that brought the Celtics and Norse settlers including the Vikings to Iceland in the first place nearly 1400 years ago. And they continue to come from as far away as America, Mexico, Thailand, Pakistan, and Tibet.

Shalimar is a small restaurant in downtown Reykjavik run by a Pakistani couple. The three person staff consisted of an Icelandic waitress, Tse-Wang from Tibet, and a waitress presumably of North African origin. Tse-Wang is a fascinating case of this migration. Originally from the remote, landlocked, Himalayan country of Tibet he was driven out from his land and forced to live as a refugee in India. Now one of only four Tibetans in Iceland, he goes to college here, learns Icelandic, and tells me that he occasionally feels lonely and isolated from a larger Tibetan community. We banter about the Dalai Lama and the Kalachakra sermon, one of the most elaborate rituals of Mahayana Buddhism. The one ironic parallel is that he once lived in country that has the nickname of “roof of the world” and he now lives in another that also feels like the roof of the world given how close Iceland is to the North Pole. Similar fascinating tales pour out from the Polish, Portuguese, Chinese, Indians, Germans, and other nationalities I meet in Iceland. Each tale of migration unique in its own way – Kathleen the German nanny who has traveled through Mongolia, Febian the Frenchman who works on a chicken farm and wants to be a monk, Marco the Portuguese who along with his father and sister work on the Karunjukkar hydroelectric project.

The world is a breathtakingly big place. Iceland in particular is imbued with special magic. Pick up your bags and go.